Hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles aren’t just fodder for science fiction or far-out R&D experiments. Cars fueled by hydrogen, like the Toyota Mirai and Hyundai Nexo, are already here, and fuel-cell technology is actively evolving and benefiting from billions of dollars in federal research and infrastructure funding. So then, why are hydrogen cars virtually non-existent on U.S. roads today? What happened?

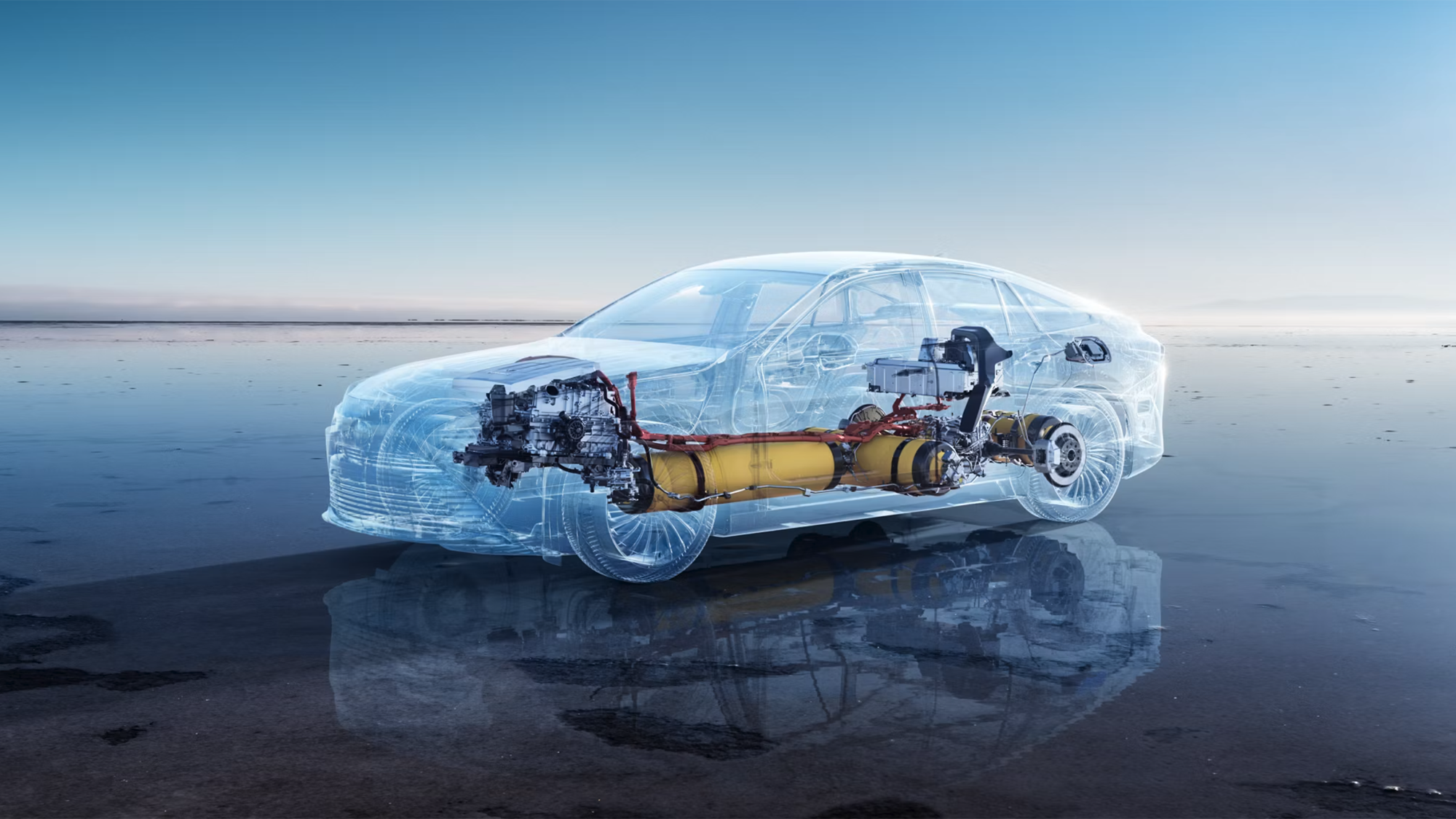

“The answer is very simple: economics,” Sergey Paltsev, a senior research scientist at the MIT Energy Initiative told Popular Science. Politicians and automakers once held up the fuel cell, which turns the chemical energy of hydrogen into electricity to drive an electric motor, as the future of passenger automobiles, but the falling cost of batteries and the upsides of a preexisting fueling infrastructure (see: the electrical grid) have propelled battery-electric cars well into the lead.

[ Related: How some automakers are still pushing ahead for a hydrogen-powered future ]

“It’s not just the cost of the car,” explained Paltsev, who is also deputy director of the MIT Center for Sustainability Science and Strategy. This is an important point, because in California, low-milage hydrogen cars sell at a steep discount.

What makes hydrogen passenger cars altogether costlier than their battery-electric counterparts is the lack of fueling infrastructure, energy-conversion inefficiencies, and the price of the fuel at the pump.

A big switch to hydrogen cars would require enormous infrastructure development; the Department of Energy’s Alternative Fuels Data Center shows 55 public hydrogen fueling station locations in the U.S. today, almost exclusively in California, next to more than 68,000 active public electric vehicle charging stations across the country. (Even in California, refueling passenger hydrogen cars can apparently be such a trial that it sparked a July class action suit against Toyota.)

In a separate call with Popular Science, Gregory Keoleian, the co-director of Sustainable Systems and MI Hydrogen at the University of Michigan, paused to double check if automakers are still releasing new hydrogen passenger cars in California. While Honda discontinued its two hydrogen passenger cars available in California in 2021, Toyota and Hyundai continue to produce new hydrogen passenger cars for sale in the state. Along with a desire for precision on professor Keoleian’s part, his pause highlights how attention on hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles has shifted from passenger cars in favor of more advantageous applications, including medium- and heavy-duty trucks and aviation.

“Battery-electric vehicles can be problematic when you have problems with range or fueling time,” or heavy loads, Keoleian said. “That’s where hydrogen can play a role with, for example, long-haul trucks.”

When it comes to things like rail and commercial trucks, “your fueling stations are more dispersed. You don’t need the concentration of fueling facilities. You don’t need them on every corner. There’s really an opportunity to decarbonize with hydrogen for those applications,” he explained.

‘Brighter pathways’ for hydrogen passenger cars

“Nothing is going to change next year, or probably not in the next five years, but there are brighter pathways for hydrogen cars,” said Paltsev. For one, if hydrogen turns out to be a “much bigger source of our energy needs in other parts of the economy, like in heavy-duty transportation and industry,” then the fueling and infrastructure challenges are “going to be easier to resolve,” providing “positive spillovers and synergies for hydrogen cars.”

Paltsev noted that the economics of hydrogen cars are already more attractive in some parts of the world than in others—citing, for example, Japan, where electricity costs are high. Several automakers are also still invested in hydrogen fuel-cell passenger cars, as evidenced by a recently announced collaboration between BMW and Toyota; the two say a BMW hydrogen production car will arrive in 2028.

The current impracticalities of hydrogen passenger vehicles in places like the U.S. are additionally not a reason to “just give up” on this particular application of fuel-cell tech, cautioned Paltsev. “We may need it for many other reasons in the future,” he added, citing geopolitical issues as a factor that could disrupt access to raw materials for batteries and make hydrogen cars suddenly more economically viable.

This story is part of Popular Science’s Ask Us Anything series, where we answer your most outlandish, mind-burning questions, from the ordinary to the off-the-wall. Have something you’ve always wanted to know? Ask us.