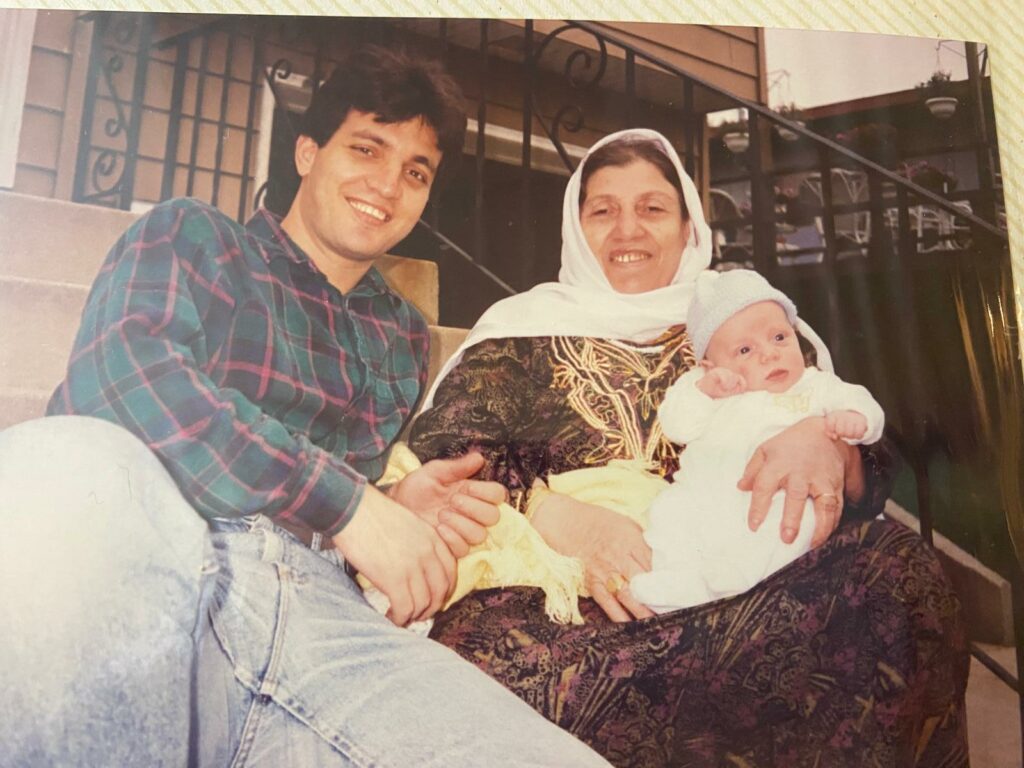

At center, the author with her father and her grandmother. Photograph courtesy of Sarah Aziza.

Occasionally, when we were small, our father spoke to us of geography.

Daddy is from a place called Palestine, he said, in a lesson captured by my mother on the family’s camcorder. In the footage, my father sits in a small rocking chair, brown eyes intent, a little shy. My younger brother and sister are absorbed by the array of blocks on the floor, but I am close to my father’s feet, my fluffy blond head thrown back, mouth pink and agape. He holds up a globe, his fingers sliding toward a sliver of brown and green. He tilts it toward me to reveal cramped lettering: Israel/Palestine.

I hop up to look, my nose nearly skimming the painted plastic as I squint at the hair-thin ink. I am vaguely aware of a thing called countries, loosely grasping that these are places full of people that are like—but unlike—me. There is no mention, today or any day that I can recall up to that point, of the first half of that forward-slashed name, that thing called Israel. There are no tales of shed blood, no wistful tributes to a lost homeland. My father simply hops his fingers, jumping decades and tragedies. Due south, he points to an orange oblong slab of land. That’s Saudi Arabia. That’s where Sittoo lives. My father uses the فلاحي word sittoo—honored lady—our dialect’s term for grandmother. I squint again, trying to see her.

My grandmother, like these countries, feels important and vague. It would be one year before she came to live with us and two years before we uprooted and moved to Jeddah, her adopted city by the sea. In our lesson, my father did not linger, did not try to bridge the difference between Jeddah and Palestine. Instead, the video shows him smiling, rolling the world to my left. He lands on a green sprawl labeled the United States. His finger taps another dot, Chicago, which clings to a lake shaped like a tear.

And here is where we live, my father concludes, his voice a flourish. Impressed by the blue distance between there and here, I blurt, Woooooah. Those are … those are two faraway places! My father looks up at the camera, his face twitching with repressed laughter. That’s right, habibti, he replies, trying to match my seriousness. The lesson ends here. I have enjoyed the attention of my father, playing with this ball called the World. But afterward, I remain just as bewildered by two photos hanging down the hall.

At the far end of a row of family portraits, these two were smaller than the rest. Daily, I passed by them, trying in vain to avert my eyes. Each time, I failed, back of my neck pricking as I raised my head to stare. The first photo is small, its frame a cheap imitation gold. Inside floats a black-and-white image of a barefoot little boy. He squints in long-gone sunshine, a crease in the photo cutting a furry line above his brow. He bears a striking resemblance to my brother, yet his wary eyes defy intimacy.

I asked my mother, uneasily, about this stranger. She informed me that this boy was my father, standing in a place called Gaza. A name with serrated edges, a word I’d not hear again until years later, buzzing on TVs. Her explanation ended there, and I felt with strange certainty that I was not meant to ask more. Instead, I studied the images—the sand and debris at the boy’s feet. Jagged shadows, bleaching light. The whole scene left me feeling both lonely and alarmed.

The second photo was better preserved, and more ominous to me. A black-and-white portrait of the same small boy with his mother, posed unsmiling side by side. The woman only vaguely resembled the grandmother I would come to know. Still in her thirties, her cheekbones were full and smooth, her thick black hair tied in a loose ponytail. She unnerved me with her dead-forward stare, the grim line of her mouth. The boy tilted toward her, regarding the camera skeptically, as if ready to defend.

These photos jarred with the others on the wall. The rest were poised, inviting, blooming from sepia to color. Shots of my mother’s childhood: a blond girl in bobby socks. A picture of her own mother, a woman with coiffed hair, hands resting on a harp. Bright photos of our young family, taken in a Kmart studio against a blue-cloud wall. My imagination roamed easily inside these frames. But I passed my eyes over the corner that held my father and his mother. Looking at them directly left me cold, swimming in something I couldn’t name.

***

My grandmother, a young woman in sixties Gaza, woke often with a thudding chest, the night tangled in her hair. With my young father in tow, she sought solace from neighborhood women. One read meaning in coffee dregs, peering into small porcelain oracles. Another, Sheikha Amna, offered prayers and protective charms to secure the younger woman’s fate. These women granted my grandmother story in the chaos of exile, reason and agency inside loss. But later she ceased searching for such solace. قدر الله—in matters of fate, it was best to contend quietly. The blue plumes of her bakhoor wafting wordless, heavenward.

In the realm of records, her trace has always been slight. Born without a birth certificate in the days of British rule, her name was first written in 1955. A UN worker made the inscription—once in English, once in French—and handed her the paper slip. Her name, a token traded for sugar and wheat, in languages she couldn’t read. She would have been roughly thirty then, a refugee of seven years, mother to a daughter and three sons.

Before, in her Palestinian village of six hundred, names were known by heart. She was bint Mohammed al-Mukhtar, ibn Yousef. Her lineage, a chain of masculine names, a tether to time and place. Her town, ʿIbdis, first appeared in Ottoman files in 1596, and may date to the Byzantine period between the third and sixth centuries, as Abu Juwayʾid.

The Ottoman officials in ʿIbdis marked down thirty-five households that year, not bothering with names. Their interest was in dunum, the rich fields yielding wheat, barley, and honeybees. Later, the villagers added grapes and oranges alongside olives, chickens, and mish-mish. Hundreds of towns like ʿIbdis dotted the rolling countryside. Each had its defining feature, preserved in stories and poetry. ʿIbdis’s boast was its jamayza, the stately sycamore tree.

Horea was the name given to her when she was born. حورية, easy to mistake for حرية—freedom. Sometimes, I wish حرية was her name. The meaning of حورية is not fixed but hovers around beautiful woman. Sometimes translated as nymph, a word found centuries back in poetry and Qurʾanic verse. In English, it can also be rendered as dark-eyed beauty. Sometimes, virgin of paradise. Some hadith, with a hint of colorism, describe a woman so gorgeous her flesh glows translucently. Is this what makes an angel? Something desired and vanishing?

Yet her girlhood was a sturdy-bodied thing. She was daughter of the mukhtar—chosen one, a mayor of sorts, a man appointed to lead village affairs. For her, mother was multiple. Horea was raised by her father’s several wives; then, after her father’s death and mother’s remarriage to a man on the Gazan coast, she was tended by a sister-in-law. There, Horea’s world was woven of half siblings, cousins, and the guests her brother Fawzi entertained.

Like most other village girls, she was never sent to school. Instead of holding pencils, her fingers grew deft at taboon dough, spark-quick as she flipped white-bellied bread over flame. As a young wife, she carried lunch daily to her husband in the field. Passing neighbors on the way, they embroidered greetings in the air. She set down the basket of bread at her husband Musa’s feet. May Allah give you strength. Receiving, he said, May God bless your hands. After eating, she yoked her afternoon to his. Together, they worked the land until evening called them in.

***

These were the days she later kept tucked inside her, hidden from my father and from me. Horea embalmed her childhood in silence, ʿIbdis shrouded in vague myth. My father would not glimpse this history until decades later, as Horea led him through its ruins, the past spelled in scattered stone. His timeline began in Deir al-Balah, a city in Gaza noted for not sycamore but its date palms. He was born there in 1960, his birth registered by the Egyptians who, in 1948, replaced British occupiers after halting Israel’s southern advance. On his birth certificate, ʿIbdis hovers in the white space around the words GAZA STRIP.

Horea welcomed her fourth and last born, Ziyad, in a UN clinic alone. Her husband was four years deep in ghourba, a post-Nakba economic exile cobbling a meager living in the Gulf. She carried her newborn home on foot, her steps jaunty, jubilant. With Ziyad, there would now be four of them sharing the two rooms Horea had built on an unused lot of land. This, a permanent makeshift shelter after months of waiting for NGO housing. The only furniture stood in the sand outside—an old table her second-born, Ibrahim, used as a desk. He was the family’s brightest, with dreams of medical school. To its left, an area for kneading dough and a banana tree that refused fruit.

Like any child, my father was born to trust. Gaza was Falasteen was home was the world. Ziyad loved the small path his days carved, barefoot, between his mother’s lap and the beach. Mornings, he woke to the coo of pigeons, a flock Horea raised and cooked on Friday after prayers. At these meals, he jostled his brothers for a double portion of meat. Above him, history webbed, conjured in the words of Horea and her guests. From time to time, he heard a moan slip from one and caught a chill. He glanced up to see his mother’s head shake, her shoulders slack. But these were only passing, distant clouds. ʿIbdis, war, and even your father—seldom spoken directly, these words had no bodies, no weight. With before locked away, he did not see his life as aftermath.

There are kinds of love that stop language in its tracks. Perhaps she held back ʿIbdis’s name to save it from the past tense. An absence spoken gathers mass, asking the body to bear it twice. Maybe her silence was a refusal, a declaration that grief should not be her sons’ inheritance. In the end, survival is a language, a logic all its own.

Yet ʿIbdis needed no speaking; it echoed in everything. It flickered in the eyes of her cousins as they circled lost acres in their heads. It lived in the sturdy music of their dialect, consonants like hilltops, memory tucked inside تعبيرات. It hovered in the taste of bread, baked from UN-issued flour. The flat sameness of its texture recalled how the dough in ʿIbdis rippled, grainy with hand-milled gamah. Each bite a morsel of the months past—rain or dryness, farmers’ worry, hands plucking, then grinding kernels of gold.

This essay is adapted from The Hollow Half, which will be published by Catapult in April.

Sarah Aziza is a Palestinian American writer and translator. Her journalism, poetry, and nonfiction have appeared in The New Yorker, The Baffler, Harper’s, Mizna, the Intercept, the Guardian, and the Nation.