Inka Essenhigh, Red Poppies, 2024, enamel on canvas, 40 x 50″. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery.

1.

The mind is always too simply seeking meaning, trying to boil some beautiful thing down to its conceptual essence.

What can stun the mind into quietness? What can briefly flummox the mind in its quest to reduce everything to a concept?

Well, a work of art can.

2.

Why should this be a good thing, this flummoxing?

Some of you may remember the song “Day by Day,” from Godspell, a musical we were wild about in (seventies, Catholic) Chicago; Godspell, in which the singer prays that God will help her to:

See thee [God] more clearly

Love thee more dearly

Follow thee more nearly

Day by day

When the mind goes quiet, we “see more clearly.” To “see more clearly” is to be in better touch with God, with that which actually is. That is, we will “love more dearly” that which actually is. “Loving more dearly” what actually is, we’ll be “following thee” (God, i.e., that which actually is) “more nearly,” which means living in a less deluded way.

And who doesn’t want some of that?

3.

Well, no need to bring God into it.

The delusion we’re trying to avoid, in order to live in a less deluded way, is the belief that our mind, through the vehicle of our senses, is bringing us the world itself and not just a rickety simulacrum of it.

But what the senses present to us really is a rickety simulacrum.

Neuroscientists tell us that, in every instant of our perceiving lives, the mind is assembling, from a continuous stream of sensory data, a cloddishly simplistic model of the world. Which is good! It helps us to stay alive! But it’s also bad, because the model we’re making is approximate and often gets made too early and with too much certainty. (We mistake the garden hose for a snake and attack it with a hoe; we mentally assemble an erroneous idea of the intentions of a friend and resolve never to speak to them again; we make a projection about another country and invade it.)

The good news is that the mind can be worked with, can be taught to recognize and delay all this form-assigning and name-giving and projection-making.

The value of a master like Inka Essenhigh is, it seems to me, that she can assist us in the virtuous slowing-down of visual perception.

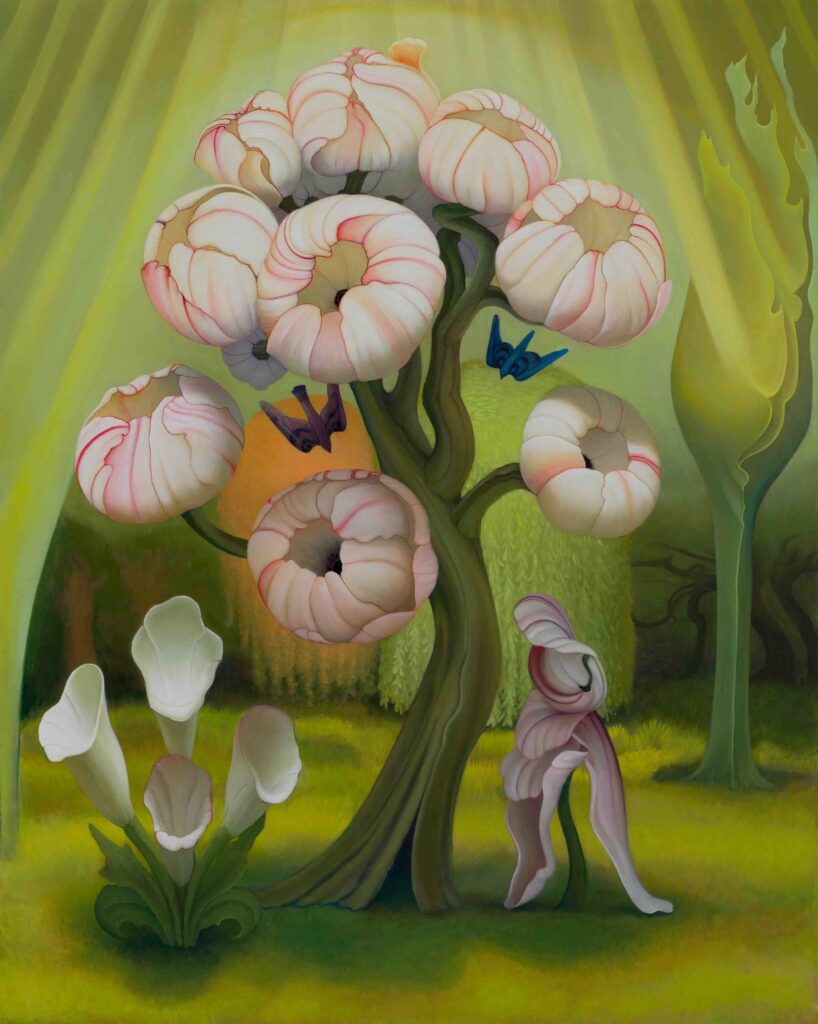

Inka Essenhigh, Flowering Tree, 2024, enamel on canvas, 40 x 50″. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery.

4.

Essenhigh sees with uncommon alertness. She notices things we don’t. Some of these things she notices are actual (wild patterns in bark, for example, in Forest Light) but some of what she’s “noticing” isn’t actual at all.

In Ghost Pipes, those two little units off to the right appear to be human. Or, let’s say, they are human-adjacent, they remind us of the human form. But they also seem pretty darn plantlike. We note that they appear to be growing out of (I’d say “standing on”) what appear to be rocks, the two of them, while admiring that Ghost Pipe off to the left. Their “bodies” seem to be made of flower stuff. So, those two strike me as living beings, out for a stroll, who’ve wandered over from some nearby flower kingdom, to see what things are like over here.

My mind struggles a bit with this, and for me this is the essential Essenhigh moment.

The thing I’m seeing is so beautiful, so overwhelmingly itself, so convincing, so intense, so confident, that I find myself transported to the border between “real” and “unreal,” and, standing there, believing in this gorgeous-though-unlikely place Essenhigh has made for me, I find myself rethinking those terms.

What’s more “unreal” than reality, closely observed? What’s more “real” than the abstract patterns we find in every single thing, if only we could abide with that thing long enough?

I don’t know what these paintings “mean” exactly, and I don’t want to: the little celebratory ripple they make in my consciousness is enough. That alteration is their meaning: I experience a brief liberation from the domination of the habitual.

5.

In some of Essenhigh’s earlier work (like, for example, Flush & Aqua or The Adoration) I felt she was spending time in the land of pure form, and, by applying a rigorous technical approach, bringing back little snapshots from that place. The forms I found in those paintings seemed more real than the things I would see when I looked away; “truer” somehow, wilder, more touched with a kind of mad yet sane level of control, funny in the way that God might be funny. They seemed to have been made by whatever or whoever had made all these external forms out here in the real world in the first place (these tables and watches and hanging-down tree branches), but with a more focused, ornery, purifying intensity.

The effect of all of this was a recalibration of my eye; the “real world” looked crazier (more voluptuous and capricious, more organized but along an invisible-to-me axis) after I’d looked at an Essenhigh.

These new paintings seem to be carrying on this work in a daring way, by inching closer to the actual.

Those Indian Pipes are so magnificently observed and “real-looking” that they make me realize how cursorily I might look at some real Indian Pipe plants if I happened to walk by some later this afternoon. I’d basically miss the whole show. Why? Well, because I’d be: “Human, en route, thinking busily of something else,” and would likely only glance at them long enough to name them, in order to dismiss them, and since I’m not the type of person who actually knows the names of flowers, my inner monologue might go something like: “Flowers, oh, yeah, wow, pretty.”

Whereas, looking at those flowers with Essenhigh’s hyperclarity, I see that those Indian Pipes are made of constituent parts, abstract forms, dimples, scars, non- flower elements that, for the moment, are hanging together in a simulacrum of “flower” but could, at any moment, blow apart, decay, degrade, bloom even further … the sky’s the limit.

Is it a “real” flower? Oh, yes, that baby is so real that it’s edging over into abstraction.

Inka Essenhigh, Ghost Pipes, 2024, enamel on canvas, 72 x 82″. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery.

6.

In Essenhigh’s work there lies a reminder that (as we Buddhists put it) “form is emptiness, and emptiness is form.”

But if form is emptiness, emptiness is also form. Reality does arrange itself into specific patterns and that is good, lovely, so much fun, if only we recognize those forms as temporary. Even as that beautiful madness in Poppies resolves itself, into, yes, poppies, it threatens to explode into pure form. Which is what “real” poppies are doing all the time, which is what everything “real” is threatening to do at every moment: revert to pure form. Every formed thing will, in fact, revert, eventually, into pure form; will die, decay, lose its current shape, be remade, reborn, repurposed.

These paintings, for me, expand out into an extra dimension, the dimension of time. These are poppies, yes, but they are also stylized poppies and flawless poppies and poppies on their best day ever, poppies so full of life you can feel the imminent death in them.

7.

Many years ago, the first and only time I ever did acid, I looked down at my hands and noticed that they were not, in fact, “flesh-colored” after all, but contained dozens of colors: pinks and purples and reds and blacks, and many other shades I didn’t have names for.

Blessed by that experience, I’ve never looked at my own hands the same way again.

I connect my memories of my hands that day and Essenhigh’s work in this way: both are holy, sacramental, because they hint at the idea that I am, simultaneously, more than my perceptions and beautifully, permanently bounded by them.

8.

A sacrament is something we engage in occasionally, ritually, the purpose of which is to remind us that the way things usually are is not necessarily the way they are ultimately.

A sacrament can wake us up, jar us back into fresh awareness of what we really are, and of the way in which we are each limited and restricted by our location within our body and mind.

Essenhigh’s work, sacramentally, reminds me that most of the time I’m coasting, on perceptual autopilot. It says: “George, let me help you see better, with more acuity and less habituation. Let me help you expand the miracle of your awareness and become a more generous noticer. Try to know less. Stay with the not-knowing a little longer; it’s nice there.”

And:

You can abide with a thing longer than you believe you can; reality won’t be as frightening or as inscrutable after we’ve paused here together a moment, having given up on trying to control everything by categorizing it into forms; once we’ve allowed reality, for a moment or two, to be (exuberantly, joyfully, in a state of overflow) itself, right here in front of us.

And:

Life is short. Why would you, George, want to go through it seeing only partially? That is, seeing things only as they happen to be manifesting at this moment, as presented by your limited viewing apparatus?

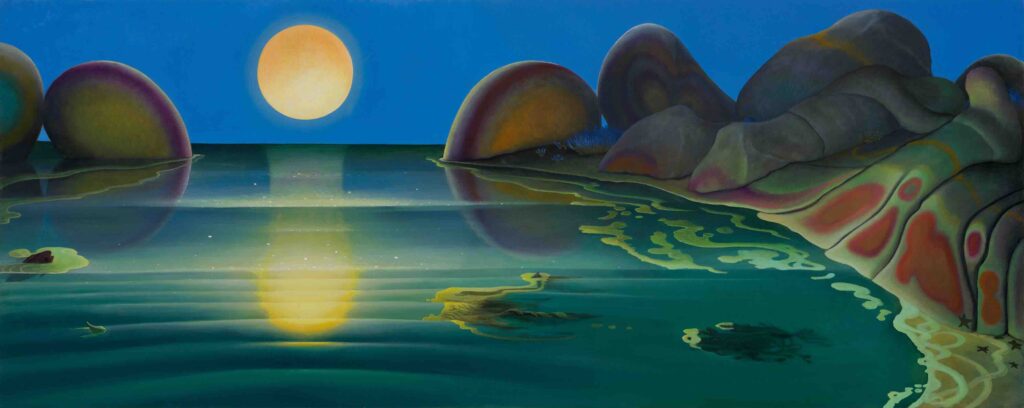

Moonlight, 2024, enamel on canvas, 32 x 80″. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro Gallery.

9.

What I feel, looking at an Essenhigh painting, mostly, is the sheer delight of invention, the sense that she is following, as she paints, something she can’t name and isn’t all that interested in naming. I find myself thinking about the beauty of overflow; about the hypnotic effect of artistic exuberance; of the mystery of the fact that, when a person is following ecstasy in this way (steering by the seat of her pants, just having some damn fun) it can lead that person into her greatest depths—can result in gifts like these paintings, which are, I suspect, in some ways a mystery to her, even, and in which, I’m betting, from my own experience, she sees evidence of something bigger than herself—wiser, less restricted, more contrary, less interested than she herself, in everyday life, might be in making sense

My years of working at writing makes me suspect that while there is, yes, actual looking involved, her process has become, for her, an enhanced way of seeing.

10.

The hyperclarity in Essenhigh’s work, that is, it seems to me, must originate in a low-judgment atmosphere. Thoughts (concepts, theories, too-overt intentions) are all forms of the noise the mind gives off when it’s busy identifying forms and giving names to them.

And this is the opposite of the open mind needed to create such startlingly original work.

What is an “open mind”?

Well, I suppose it’s a mind not cluttered with thoughts, or an agenda, or a big damn plan. (“Not knowing is most intimate,” goes the Zen koan.)

However, if we pause for even a second and try to attain such a mind, we’ll find it’s nearly impossible.

One way of trying to attain such a mind, if only for a few minutes a day, is by way of a rigorous artistic practice.

11.

Sometimes, when I’m writing a story, the language starts leading me, rather than the other way around. A certain sentence wants to be adjusted. Why? Well, sound, mostly. I feel a more energetic version of the sentence hiding there inside the torpid version. So I just … change it. I make that change purely because I feel like it, because it’s fun to do.

Then, lo and behold, that little linguistic adjustment changes the whole story.

Hooray, I think, I’ve just outfoxed my conceptual mind: this story is no longer the one I’d planned to write.

That’s the moment I live for in my art, the moment when I see there is more to me than just everyday me, that I have access to, yes, a higher wisdom, and I can only get there by craft and hard work.

I find some confirmation that Essenhigh and I might work similarly, in this, which she offered in an interview, asa way of explaining a certain technical swerve she’d made:

“I thought this way of working would be exciting.”

Amen to that.

Amen, also, to this: “I don’t think the world needs another okay-looking painting that doesn’t have a sense of purpose, love, and completion.”

Exactly: the world needs the purpose, love, and completion we see here.

Because the world, our lovely world, is being choked to death by the opposite of “purpose, love, and completion”: by ego, rapaciousness, intellectual inexactitude, and a hideous neglect of the kind of passionate rigor we see modeled in these paintings.

The kindest thing a person can do for another person is to remind them, by example, that purpose, love, and completion can still, even yet, be achieved.

So, thank you, Inka Essenhigh, for reminding me of this, and for expanding my ability to see the world more clearly, and therefore to love it better.

This essay is excerpted from Inka Essenhigh: The Greenhouse, published by Victoria Miro. An exhibition of Essenhigh’s paintings is on view in London through April 17.

George Saunders is the author of Lincoln in the Bardo, which won the 2017 Man Booker Prize, and, most recently, a short-story collection, Liberation Day.