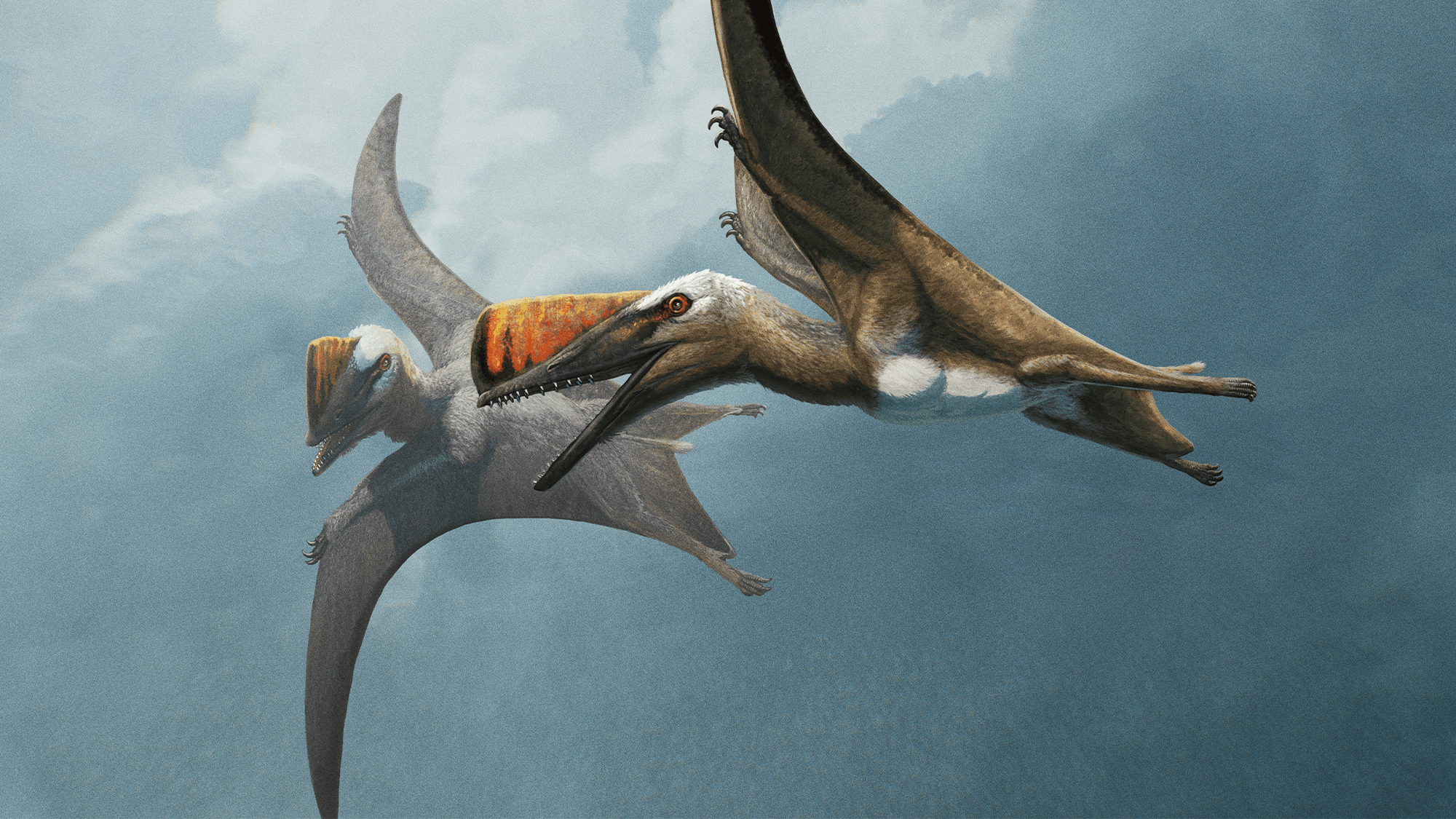

The pterosaurs that flew across prehistoric skies while dinosaurs walked the Earth came in all shapes and sizes. Some, like Cryodrakon boreas, boasted an enormous 32-feet wingspan, while other earlier pterosaurs had a more dainty 6.5 feet wide wingspan like a modern harpy eagle. Now, a newly discovered pterosaur species is helping explain this leap from a smaller to larger wingspan size and other physical changes. Skiphosoura bavarica is described in a study published November 18 in the journal Current Biology.

For paleontologists, Skiphosoura bavarica shows how these winged reptiles may have changed over time. Skiphosoura bavarica means “sword tail from Bavaria,” because it was discovered in southern Germany and it has a very unusual short, stiff, and pointed tail–similar to a sword. The specimen is complete, meaning nearly every single bone is preserved. Importantly, the bones are also preserved in three dimensions, where most pterosaurs tend to be crushed flat over time. When it lived, it would have been about the size of a golden eagle with a wingspan of about 6.5 meters.

For 200 years, paleontologists split the pterosaurs into two major groups. The smaller and earlier non-pterodactyloids and the later and much bigger pterodactyloids. Early pterosaurs sported short heads on short necks, a short bone in the wrist of the wing, a long fifth toe on the foot, and long tails. The later pterodactyloids had the opposite–large heads on long necks, a long wrist, short fifth toe and short tail. Which parts of their body changed and when remained a mystery.

In the 2010s, paleontologists found several intermediate species called darwinopterans. The specimens revealed that the head and neck changed first before the rest of the body. The darwinopterans were a solid example of an intermediate that bridged an evolutionary gap. However, even with this bridge, we didn’t really know what was going on before or after these changes.

[Related: ‘Remarkable’ fossils offer clues to perplexing pterosaur question.]

The Skiphosoura bones reveal these changes. On an evolutionary timeline, Skiphosoura sits between these earlier darwinopterans and the pterodactyloids. It has a very pterodactyloid-like head and neck, but also has a longer wrist and a shorter toe and tail than earlier darwinopterans, but these are not as long as we see in the later pterodactyloids.

Along with the discovery of a completely new species, comes a new reconstruction of the pterosaur evolutionary family tree. Skiphosoura shows a middle position on the family tree, but also reveals that a Scottish pterosaur genus–Dearc–is in a similar middle position between the early pterosaurs and the first darwinopterans.

[Related: This pterosaur ancestor was a tiny, flightless dog-like dinosaur.]

The discovery means that paleontologists now have a complete sequence of pterosaur evolution–early pterosaurs to Dearc, to the first darwinopterans to Skiphosoura, to the pterodactyloids. Even though not every pterosaur specimen ever found is quite as complete as Skiphosoura, we can now trace the increase in head and neck size, the elongating wrist, shrinking toe and tail, and other features step-by-step across multiple groups.

Both Dearc and Skiphosoura are unusually large for their time, which suggests that the changes that allowed the pterodactlyoids to reach enormous sizes were already appearing in these transitional species.

“This is an incredible find. It really helps us piece together how these amazing flying animals lived and evolved,” study co-author and Queen Mary University of London paleontologist David Hone said in a statement. “Hopefully this study will be the basis for more work in the future on this important evolutionary transition.”