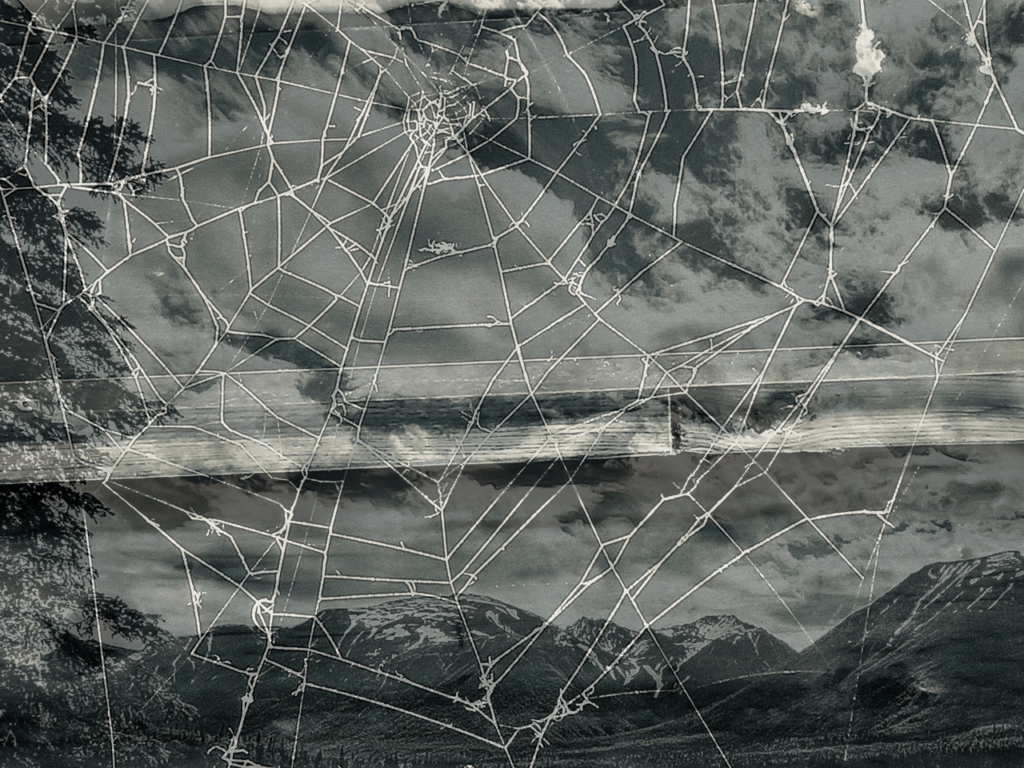

Photograph by Emet North.

We travel to Lake Clark, Alaska, in a four-seater prop plane—my partner and I, the pilot, and the housekeeper for the residency where we’ll be staying. When asked which seat he wants, the housekeeper says, “I’ll take the leg room, I’m a big bitch.” I think, Queer? I ask about his work and over the racket of the plane he shouts that he performed for a decade as a drag queen at a famous Los Angeles bar. He quit during COVID. “People are gross,” he says. Though later he will tell me it was performance itself he tired of, finding it antithetical to intimacy.

My partner, R., and I have come to the residency with the intention of inhabiting new metaphors for intimacy. In our application, we wrote, “In 1991, Lynn Margulis coined the term holobiont to describe miniature ecologies consisting of a host organism and their microbiome. The human is a holobiont—more than half of the cells in our body have nonhuman DNA.” We wrote, “In this project, we will ask how this theory of the holobiont can create possibilities for queer joy.” We’ve considered, for example, replacing the phrase “I’m full” with “My gut bacteria have multiplied by a billion and are satiated.” We know we will sound ridiculous. As we fly, I try to inhabit this new mode of thinking. I put a hand on the back of the seat in front of me and think, Look at those microbial skin communities. But the thought glances off; it won’t stick.

When we arrive, the manager of the residency gives me a choice of daily chores—laundry or knocking down spiderwebs from the eaves. I choose the spiders.

Niche is the word I have in mind the next day as my hands swing a broom at a rack of antlers. The housekeeper walks past, playing Mariah Carey on a personal speaker. “The reason you have that job,” he says, “is that I refuse to do it. I refuse to destroy another being’s home. You are going to come away with a fine sense of guilt.” The last resident who spidered experienced an existential crisis. The spiders are tenacious. They rebuild.

As is typical of species living on islands or mountaintops, each member of the lodge has an expansive niche. There are eleven of us—five residents, six staff. The plumber is also the first responder. The chef also carves the decorated wooden spoons used to ladle water onto the rocks in the sauna. The Sierra Club masculinity I expected is largely absent, replaced by possible queerness. The wilderness guide (also the guest-services coordinator) has multiple partners and talks openly about sex work. The landscaper tells us that all the Los Angeles queers are currently listening to country music. When the handyman-cum-helmsman-cum-woodworker takes off his boots to cool his feet in the lake after a long hike, his toenails are painted a vibrant blue.

At dinner that night, the housekeeper asks R. and me how he can tell us apart. We laugh. At the residency, we move as a unit—from writing desk to paddleboard, from paddleboard to hammock, where we read the same books. We arrive together at dinner. We shower together. I worry this could be unhealthy. I was once called toxic, and ever since I’ve maintained a certain vigilance. When I read articles about healthy relationships, they emphasize maintaining your sense of self, enforcing clear boundaries. R. shrugs at these maxims, says, “It’s ableist to think a healthy relationship can only look like one thing.” The self, hard boundaries—these are precisely the things we’re hoping to trouble. “It has become increasingly clear that individuality is a myth,” we wrote in our application, referencing Scott Gilbert, who deconstructs six categories of individuality and argues that every body is an ecosystem, a multispecies assemblage. In this sense, our Alaskan we is a victory.

The insects are the first to distinguish between us. After dinner, walking along the lakeshore, I wonder out loud if I’m being gendered by the mosquitoes. Studies steeped in binary sex insist that mosquitoes are more drawn to men than to women, because of their larger size and higher metabolic rate, unless the woman is pregnant, in which case they are most drawn to her. R. and I are neither men nor women and neither of us is pregnant, but when we walk through the same patch of forest, I emerge with a dozen swelling bites, and they emerge with none.

Two weeks later, three welts appear in a line on my left hand. I don’t know what bit me, don’t feel the bites themselves, but my fingers become uncomfortable, then stiff, then fully immobile. Theories as to who did it abound among the lodge’s residents. An overwhelm of mosquito bites. White sox flies. An extreme reaction to devil’s club. A spider. This last hypothesis appeals to me, because it suggests some karmic justice. It is week three of the residency, and my hands have knocked down some two hundred webs. I’ve come to know the spiders—the red-and-black-bodied one who weaves above the solar panels; the long-armed brown one, whose tattered web once caught and held an adult wasp; the fat gray one spinning high on the eaves, who waves their front legs at the broom as it comes.

The pain swaddles each finger. Not pure like the pain of an ant bite, that thrilling one-note zing, but something discordant and serrated. I had thought I was stoic, but this, like so many of my ideas of myself, proves untrue within partnership. At night, I thrash until I wake R. “It hurts,” I say. I tremble. I refuse to walk the four hundred yards to the shared kitchen for ice. I scratch, and the pain doubles down, cutting deeper. I yelp. I am dramatic, entranced by this aspect of partnership, new to me, the useful performance of physical pain.

For relief, I submerge the bites in the lake water, which the salmon scientists have measured at thirty-eight degrees. The opposite of pain is pain—a searing, water-chapped cold.

Does the creature that bit me experience a similar discomfort? Arthropods have nociception, so they know when they are injured, but as one entomology article asks, Is it pain if it doesn’t hurt? To an insect, tissue damage might register as a neutral sensation like the press of a railing against a rib—present, but neither good nor bad. There is no biological reason why recognizing tissue damage must be painful, no biological imperative for suffering.

The physicist Randy Baadhio insists that pain is a quantum thing, a harmonic oscillation which travels from cell to ready cell via resonance—like a seismic wave or an earthquake. On the third night, the worst night, I think I feel pain like that—the shaking in my hand a seven on the Richter scale, causing stone to crack, structures to collapse. When the bite punctured dermal cells, the hand’s ecosystem was overrun with thousands of neutrophils, which left their cradle of bone marrow for a riverine system of blood vessels. Now, in the fingers, the neutrophils morph like salmon do in the residency’s bay—changing color, growing a long jaw. This physical change is brought on by a chemical gradient— for the neutrophils it is due to an excess of cytokines, for the salmon to a lack of salt. In both, the transformation is a sign of maturation, of readiness to fuck and fight. Neutrophils fight by tossing highly reactive oxygen molecules toward a harmful microbe, which is destroyed in an explosion upon impact. The interstices of our hand are dotted with fireworks that no one can see. I say “our hand” because the appendage—swollen, immobile—seems to belong as much to the microbes as to me.

This is what I remember wanting to tell R. that night—I had done it, had inhabited, for a few hours, our innermost ecologies. I’d felt the microbes move through the channels of our hand. I called R. to where I stood, to tell them about this, mosquitoes biting my exposed legs and face, hand in the cold water.

R., who came bleary-eyed and panicked to the door, remembers it differently—the redness of my hand, my body contorted. R. has a different word for the enraptured preoccupation of those days—misery.

The next night, R. says, “You have to let me sleep, okay?” I agree. My nights are patterned—ice pack, cold water, moments of calm and moments of frustration. I’ve kept R. awake. “Is this toxic?” I ask. They say, “It’s toxic to ask over and over whether something is toxic.”

Some painful venoms have low toxicity. In these, the pain is a false signal, a lie. In other venoms, toxins are injected alongside pain-producing compounds. Metalloproteinase, which causes dermal cells to wither. Potassium, which depolarizes cell membranes. In these cases, when toxins are present, the pain is denoted “true.” I can’t write down, here, whether the pain in our hand is true or false. The neutrophils know, as they migrate toward the bites; their measurements are both sophisticated and inhuman, though their DNA is human DNA. They know precisely how the ecology of our hand has changed. Within the hand lies evidence of a split world—the pain is only true or false, not both. But I don’t know which. Practically, it hardly matters. It’s been several days. My hand is swollen, but I’m otherwise fine. If the venom was toxic, the toxin is localized—not systemic, not deadly. Not something, I argue to R., that merits a trip to the clinic.

Karen Barad, in her essay “Nature’s Queer Performativity,” writes that toxicity, like queerness, like gender, is an ecological identity—temporary, fluid, performative. I perform genderqueerness, and whether that gender is true or false, my person is changed. Our hand performs pain, and whether the pain is true or false, the venom toxic or nontoxic, our hand is changed.

This is the argument R. uses to insist that we should make the trip to the clinic.

Everyone can tell, by this point, who is who. I am the irritable, wounded one, the one skipping dish duties to submerge our hand in the lake. I am the one talking at dinner about a wasp that stings predators with a contorted penis.

R. is the one tying my shoes and cutting the sleeve of my rain jacket wider. R. is the one explaining my symptoms to the resident first responder. “Regardless of toxicity,” the first responder says, “the pain of swelling is true. Pressure on your nerves,” he says. “The nerves can withstand it, but only temporarily.” I return to him when the pain subsides, thinking this is a sign of healing, but he says, “A silent neuron is a dead neuron.” Then there is the rupturing of capillaries, small puddles rising to discolor the skin of our fingers. R. is the one asking about nearby clinics. R. is the one who, when I talk about the bite as intimacy, says, “You barely leave the cabin.” This is true. Our hand pulses a warning when I try to hike. Our hand can’t hold a paddle. Our hand sears in the hot water needed to wash dishes. I’ve been taken off the chore list. I’ve dropped out of the lodge’s ecology. “Intimacy,” R. says, “with who?”

Aged neutrophils return to the bone marrow, where they were born. The word for this is the same word used for salmon returning to their birth sites: the neutrophils are homing. In the bone marrow, if the body is uninjured, unstressed, the aged neutrophils are ingested by local macrophages, and their biomaterial is used to create new neutrophils. When infection or injury is present, senescent neutrophils may not be ingested but instead reenter the bloodstream, migrating back to the site of infection. I like this image of longevity, of the aged cells continuing.

When I say this to R. in the morning, they reply, “It looks worse.” The swelling has moved past the wrist into the arm, the whole limb red and spongy. “You need steroids,” R. says. But I am curious. I want to let it play out. I say I trust the microbes. “This is an allergic reaction,” R. says. “By definition, it’s not something you can trust.”

Maybe I don’t want to go to the clinic because the microbes don’t. From what I’ve read, you cannot overstate the effect of microbes upon your decisions. Suddenly craving blueberries? That’s your microbes after a little fiber. Woozy with love? Microbes flooding your brain with oxytocin. Like the smell of someone of the same gender? You’re not queer—your microbes are, attracted to the pheromones her microbes create after ingesting her odorless sweat. An article in Frontiers in Nutrition—“Romantic Relationship Dissolution, Microbiota, and Fibers”—even hypothesizes that the sadness felt after romantic relationship dissolution “might be related to decreased microbiota diversity … which could be corrected with the ingestion of dietary fibers with an additional antidepressant benefit.”

If I go to the clinic, if I accept steroids, our hand will shrink. I will lose my sense of the ecological, the new lens offered by pain. “Isn’t this what we wanted,” I say to R., “what we were trying to achieve? Inhabiting a new metaphor?” “You can’t sleep,” R. says. “You can’t work. I’m leaving in two days, who’s going to tie your shoes? If this is what it looks like to understand your body ecologically, that metaphor is dysfunctional.” “In this world, maybe,” I say. “In a world defined by individuality, maybe.” R. says, “You’re miserable, I’m miserable.”

The clinic is in the same building as the post office—across the lake, at the end of the runway, a ten-minute walk from the boat ramp, past a burger stand run by Billy Graham’s son and two hangars for the National Park Service. The nurse prescribes steroids and tells me to come back if symptoms don’t improve in forty-eight hours. If our hand requires a trip to the hospital in Anchorage it will cost four hundred dollars to get there, which I don’t have. She tells me to be careful. “If you’re bitten again by the same thing,” she says, “you could be in trouble.” She is talking about allergy, airways, anaphylaxis. But the relationship she describes between immune system and venom reminds me of infatuation. “Keep an eye on it,” the nurse says as I leave, as though she understands how alien our hand has become.

The day after we visit the clinic, R. leaves for a conference. My pain goes with them—or, at least, I lose my motivation to act it out. Our hand throbs, but there is no reason to whimper, to thrash in an empty bed. On the steroids, the topography of our hand shifts—our bones are once again visible, small buttes on the side of the hill of our wrist. I can straighten our fingers. Our hand still aches, still holds heat. The wrinkles are deeper and differently ridged—excess skin folding back on itself, just as valleys changed by flooding remain changed long after the waters have receded.

On the summer solstice, the residents of the lodge light a bonfire. They make time-lapse videos. They dance, easy with one another, secure in their niches. Their ecologies spiral around me, never quite touching me. I dance without pain, again experiencing myself as a singular being. I toss back tumblers of tea made from raspberry leaves without considering my gut bacteria. This continues until a sound artist approaches to ask if I miss R. “When does she get back?” he asks. I correct the pronoun out of habit—“They get back in a few days.” He bends toward me, lowers his voice, says, as though offering intimacy, that they-and-them pronouns are hard for him. “Isn’t it plural,” he says, “grammatically? Aren’t you a writer? Help me understand how it’s grammatical to use they and them for one person.”

Without thinking about it, I’ve lifted our hand. I’m rubbing the skin that surrounds the bites where new bacteria amass on the crusted welts.

I am quiet long enough that he apologizes. He didn’t mean to offend me. I drink a last tumbler of sun tea and retreat to my cabin. Even there, in the quiet, I can no longer feel the microbe communities pulsing. I call R. When they pick up, I’m crying. “What’s wrong?” they ask, and I tell them I’m alone.

R. returns three days later. They ask how my hand is before asking how I am. My hand is desolate. Healing is an accumulation of small deaths—bacterial cells combusted, dead cells sloughed. I’ve been considering the nurse’s words, that the microbes within the hand remember what bit it. I want to kindle that spark of recognition. I say, “I need your help.” They raise one eyebrow, an expression of skepticism.

The next day, we paddle to a secluded spot along the pebbled beach, and behind a tangle of driftwood I strip away my clothes. In a moment, I will lie my body down on the pebbles that shelter dozens of spiders. R. is the only one who will see me: we are far from the lodge, and the salmon scientists come only on Tuesdays. Nonetheless, this is a performance. I perform readiness, willingness. The spiders perform absence—they crouch in slivers of shadow, disappear into crevices. The pebbled beach, usually overrun with spiders, performs stillness. Performances help with courage. If a spider bites you during a performance, is the bite even real? Has it happened in real life, that place of lasting consequences? To insist upon performance, there is a camera. R. holds it. R., who has said, “I hate every part of this plan. I want it on record that I’m doing this because I love you. If a spider crawls on you, I’m going to lose my mind.”

The first itch is a conjuring. I lift my ankle. Nothing there. How long has it been? I ask. Forty seconds. Spiders live seven years on average. Forty seconds of my life equate to ninety minutes of theirs. How long until their fear gives way to curiosity? A tickle at the base of my neck, which I swat. I regret the swat. Nothing crunches beneath my fingers, so perhaps this itch was also a phantom. How long? Sixty seconds.

Later, returned to internet access, I’ll learn that the spiders of Alaska are not so venomous. None of their bites regularly cause major reactions in humans. R. is unsurprised. “Everything in Alaska that bit you bit me,” they say. When I apologize for my unwillingness to go to the clinic, for the way the bite came between us, they’ll say, “It didn’t. You were miserable, so we were both miserable. That’s intimacy.”

But on the beach: something moves in the corner of my eye, and my body jerks, wanting to flee. R. breathes in. A large wolf spider moves jerkily across the pebbled beach, attending to the motion of the air and to light. It tracks along the shadow of my wrist, nearly touching my skin. I wait for it to mount the boulder of my lower arm, and at that moment our hand pulses. Later I’ll learn this is a reaction to sunlight, to heat, but I believe then, with jubilation, that it’s a response to the spider, a microbial readiness.

I’d like to write it this way: the spider walked the length of my arm, the hydraulic tick of their legs making the nerves sing. Their eight eyes met four. R.’s eyes and mine watched them with breath held. But in truth, the spider, perhaps drawn by a vibration elsewhere or startled by my minor movements, scuttled beneath a rock, retreating into conspecific community, and after six minutes I, too, retreated. Went for my clothes, for R. No spiders crawled on me. But for an hour or so after, the flesh of my back held the imprint of the pebbles. The microbes on my back were temporarily more like the beach, more like the spiders.

Morgan Thomas’s first book, Manywhere, was published by MCD in 2022. Their work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Kenyon Review, American Short Fiction, and elsewhere. Their short story “Everything I Haven’t Done” appeared in issue no. 249 of the Review.