To avoid people, mountain lions (Puma concolor) in the greater Los Angeles area are changing their activity patterns. The big cats that live near areas where humans hike, run, and cycle are becoming increasingly more nocturnal than the mountain lions who live in more remote areas. The findings are detailed in a study published November 15 in the journal Biological Conservation.

“People are increasingly enjoying recreating in nature, which is fantastic,” study co-author and University of California Davis Ph.D candidate Ellie Bolas said in a statement. “This flexibility we see in mountain lion activity is what allows us to share these natural areas together. Mountain lions are doing the work so that coexistence can happen.”

[Related: How to survive a mountain lion encounter.]

Mountain lions are top carnivorous predators that eat a wide variety of meat including deer, wild pigs, rabbits, and coyotes. While mountain lion attacks on humans are rare, they can still be dangerous to hikers, runners, or cyclists who spend time in their habitats. The mountain lions in the Los Angeles area face numerous challenges–busy roadways where they’re often hit by cars, the threat of wildfires, exposure to rodenticide, low genetic diversity, and a fragmented habitat. Generally, mountain lions prefer to avoid humans altogether. But in a metropolitan area home to more than 18 million people, the natural spots where mountain lions and other wildlife live are also heavily used by recreationists.

In the new study, the team was curious to see if and how mountain lions were adjusting their activity in response to recreationists. They monitored the movements of 22 mountain lions in the Santa Monica Mountains and the surrounding region of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area between 2011 and 2018.

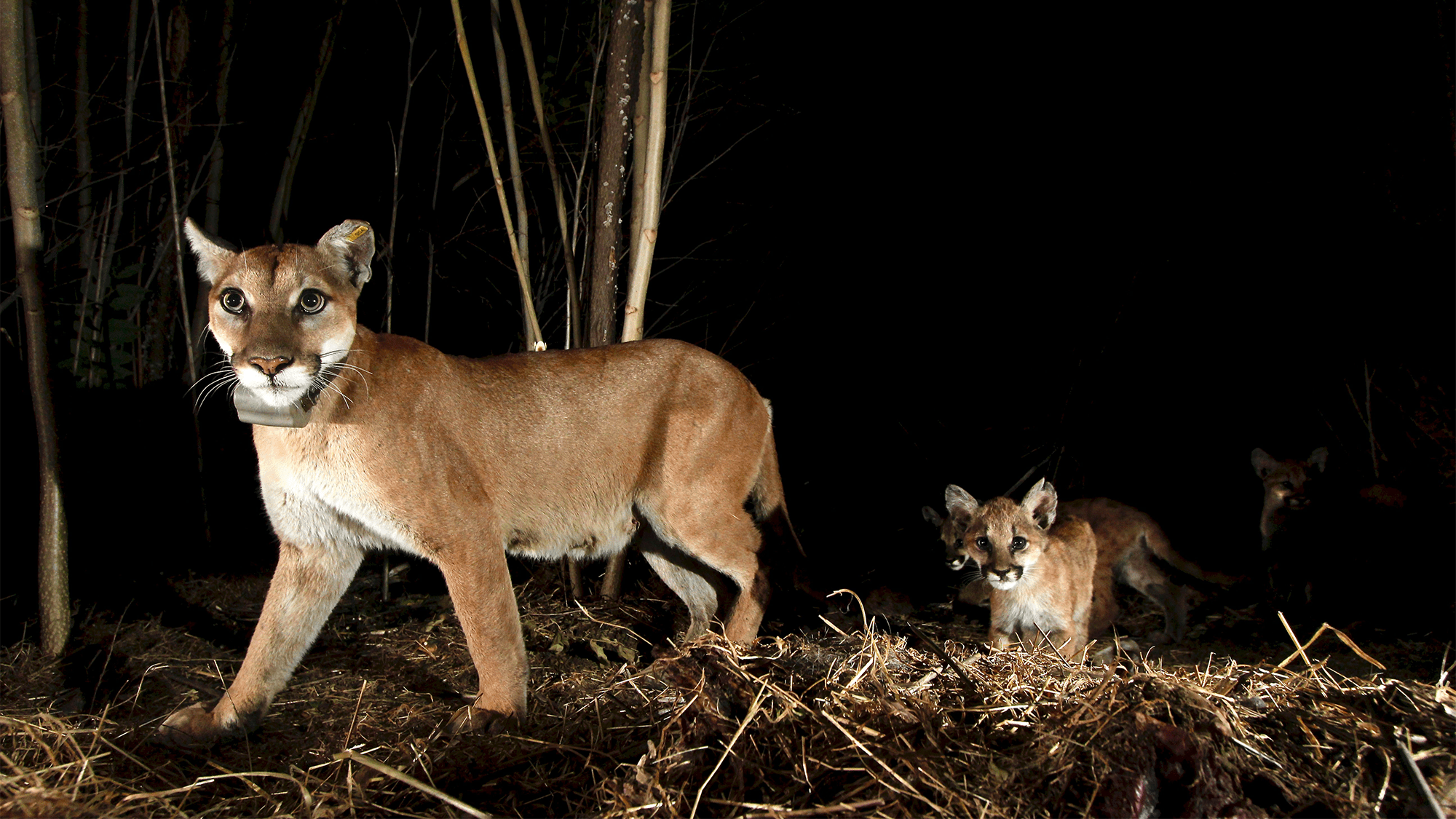

The lions were also fitted with a GPS and accelerometer collars as part of a long-term study conducted by biologists from the National Park Service. The team analyzed the collar data and quantified how much human recreation was present in the area using a database of GPS-tracked activities that users opted to make public.

Verdugo Mountains near Los Angeles, an area with high levels of human recreation. CREDIT: © National Park Service.

“These results are really important in that they show how humans may be affecting wildlife in less obvious ways than killing them with vehicles,” Seth Riley, a study co-author and the chief wildlife ecologist for Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, said in a statement. “The study also continues to drive home the amazing fact that a population of a large field predator persists in one of the largest urban areas in the world. That would not be possible if mountain lions weren’t able to adjust to human activity in ways like this.”

The results showed that Griffith Park had the highest levels of recreational activity. The Santa Susana Mountains and Los Padres National Forest were least active. Mountain lions in these more remote regions were also typically more active at dawn and dusk.

Female mountain lion P13 in the central and western Santa Monica Mountains was the least nocturnal animal. In general, the females were more active closer to sunrise and during daylight hours compared to males. According to the team, this is potentially so that they can avoid overlapping with male lions, who can pose a threat to them and their young.

[Related: Culver City is home to a unique cat versus coyote conflict.]

The most nocturnal animals were two male mountain lions that live in small, isolated natural areas with many trails, high levels of recreation, and surrounded by human development and freeways. Both individuals also had two of the smallest home ranges ever recorded. The study’s most nocturnal lion–a male designated as P41–lived in the Verdugo Mountains, a small mountain range that spans several cities.

One of the region’s most famous mountain lions–P22–preferred to stay out of the spotlight. The “Hollywood Cat” managed to make it across two busy freeways as a young lion to earn local fame and a home in Griffith Park. P22 was the second most nocturnal lion studied and one of the oldest cats in the study. He died in 2022 when he was roughly 12 years old.

more nocturnal. CREDIT: © National Park Service.

According to the team, urban experiences of P41, P22, and the others in the study shows how mountain lions will seek to avoid people rather than becoming habituated to them. They also believe that these findings offer a hopeful example of coexistence between human and wild animals in a dense human population.

However, it’s not only up to the mountain lions. People have a role in helping protect themselves, their pets, and mountain lions by being aware that dawn or dusk is prime time for mountain lion activity. The authors also urge caution when driving at night, when mountain lions living in populated areas are more likely to be active.

“Even something as innocuous as recreation can add to these other stressors we’re bringing into their lives, potentially by altering the amount of energy they have to expend for hunting and other needs,” Bolas said. “But we can feel a sense of optimism that they are flexible in the timing of their activity. Coexistence is happening, and it’s in large part because of what mountain lions are doing.”